MEMORY SPRING

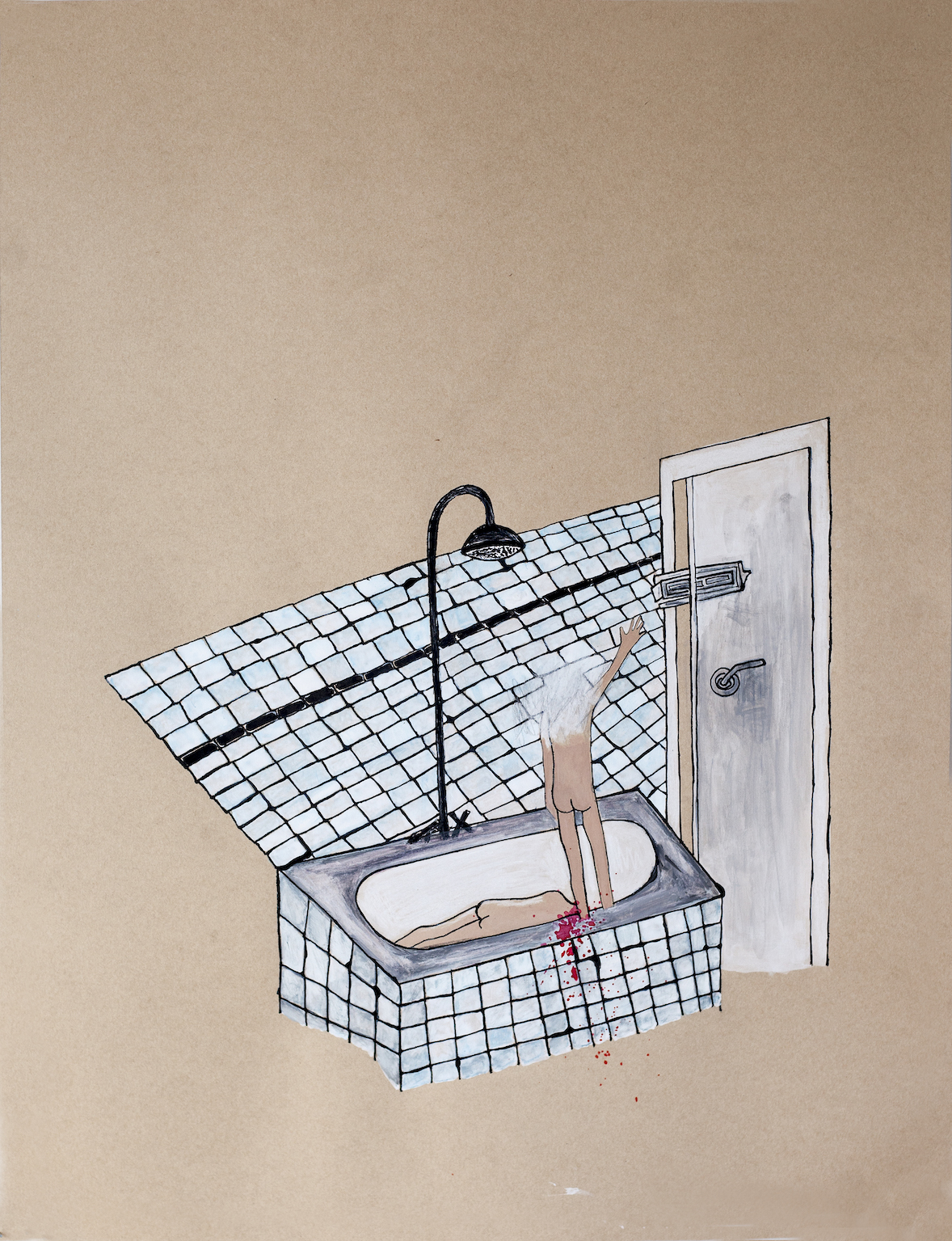

Solo exhibition in SIM Gallery, Reykjavik, Iceland 2018In 2012, amid the Arab Spring, Nermine el Ansari was living in Cairo, Egypt, and experiencing the new curfew because of the many protests. The curfew was set from 6 pm to 6 am and lasted two months during the summertime. During this restriction, she began to think about childhood memories, especially those before age 10 ( when Nermine, born in France, moved back to Egypt). She began to draw them from memory as they appeared in her mind.

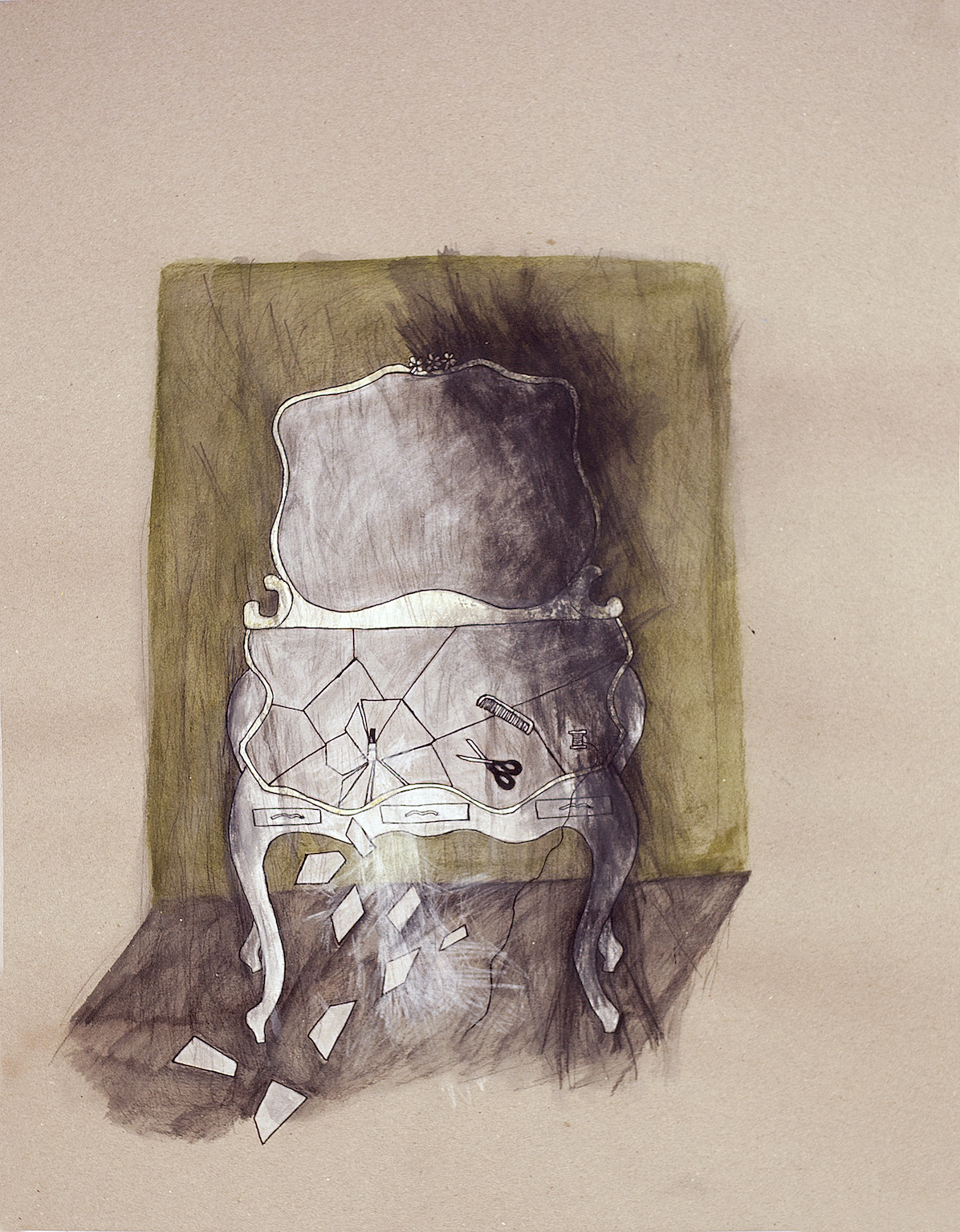

“When all is in ruins,” Nermine says, “we must return to memories.” Perhaps it is also the added effect of having your own rhythm of time manipulated by outside forces that one feels the urge to return to a place outside of time; memories. Ruins are also places outside of time, while also speaking of the passing of time.

After her first residency in Iceland in 2014, she invited a group of Icelandic artists to share photos and discuss the memories associated with the photos. The artists were asked to speak only about the images that the others had brought and no one was allowed to talk about memory itself. With an international group of artists in residency in Iceland, Nermine followed the same formula. And again, the same process was repeated in Cairo in 2015 with a group of Egyptian artists. It is from the comments taken during these discussions that Nermine wrote the texts accompanying the images brought from the different groups, which you can find on the center table of the exhibition.

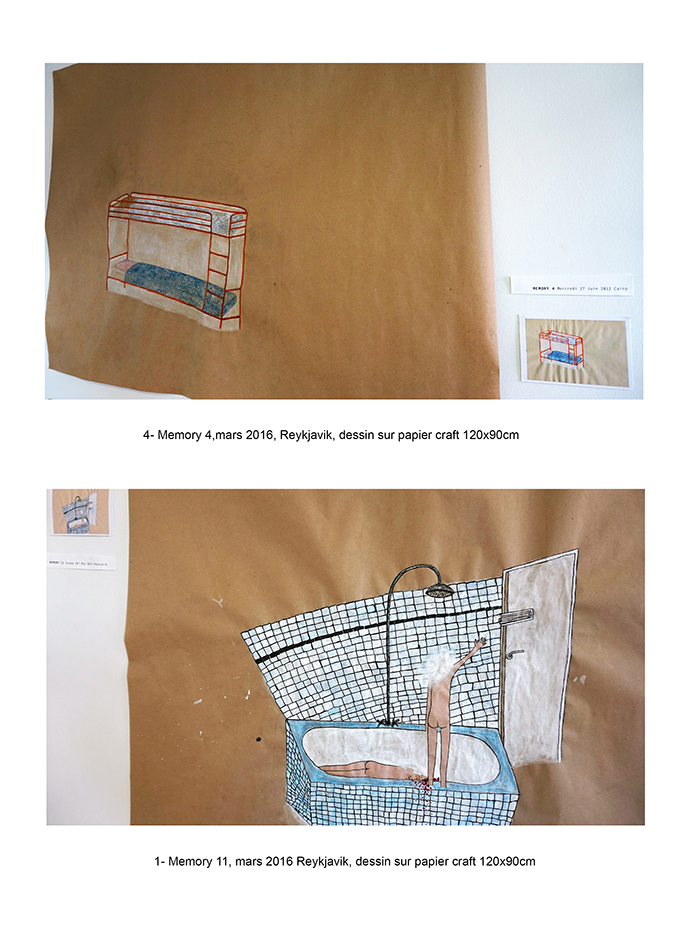

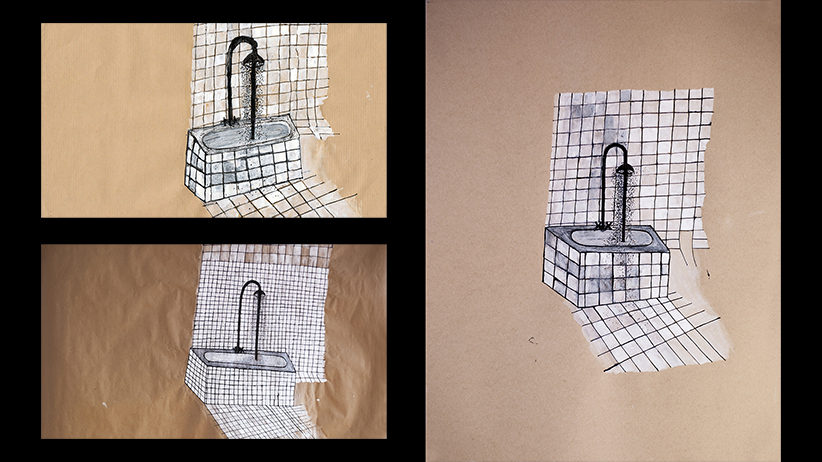

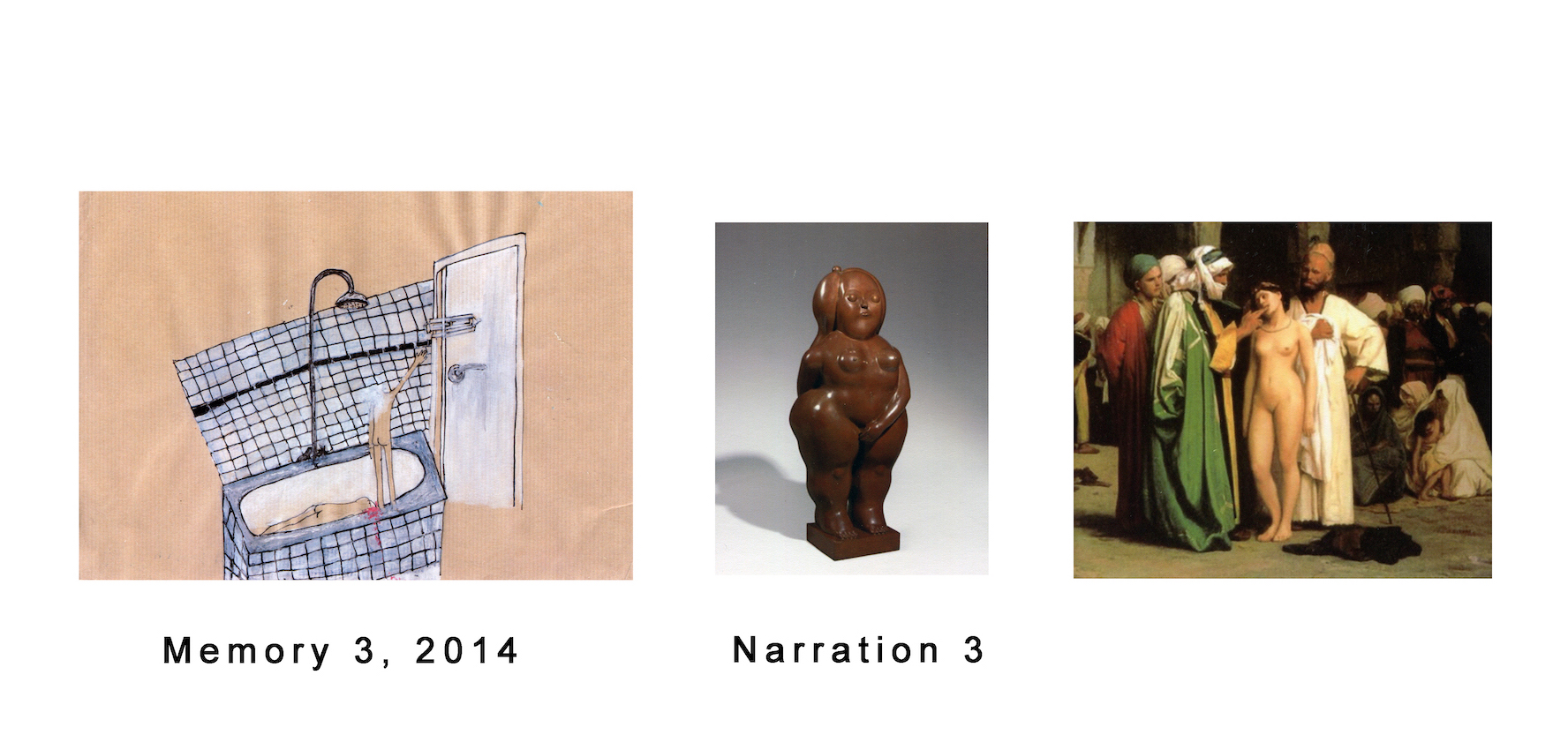

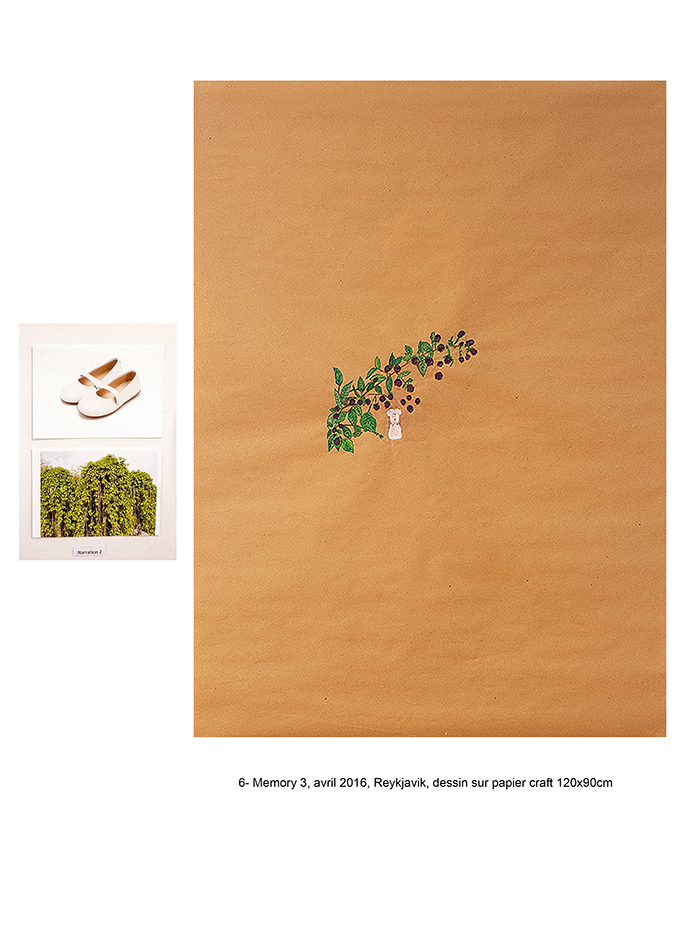

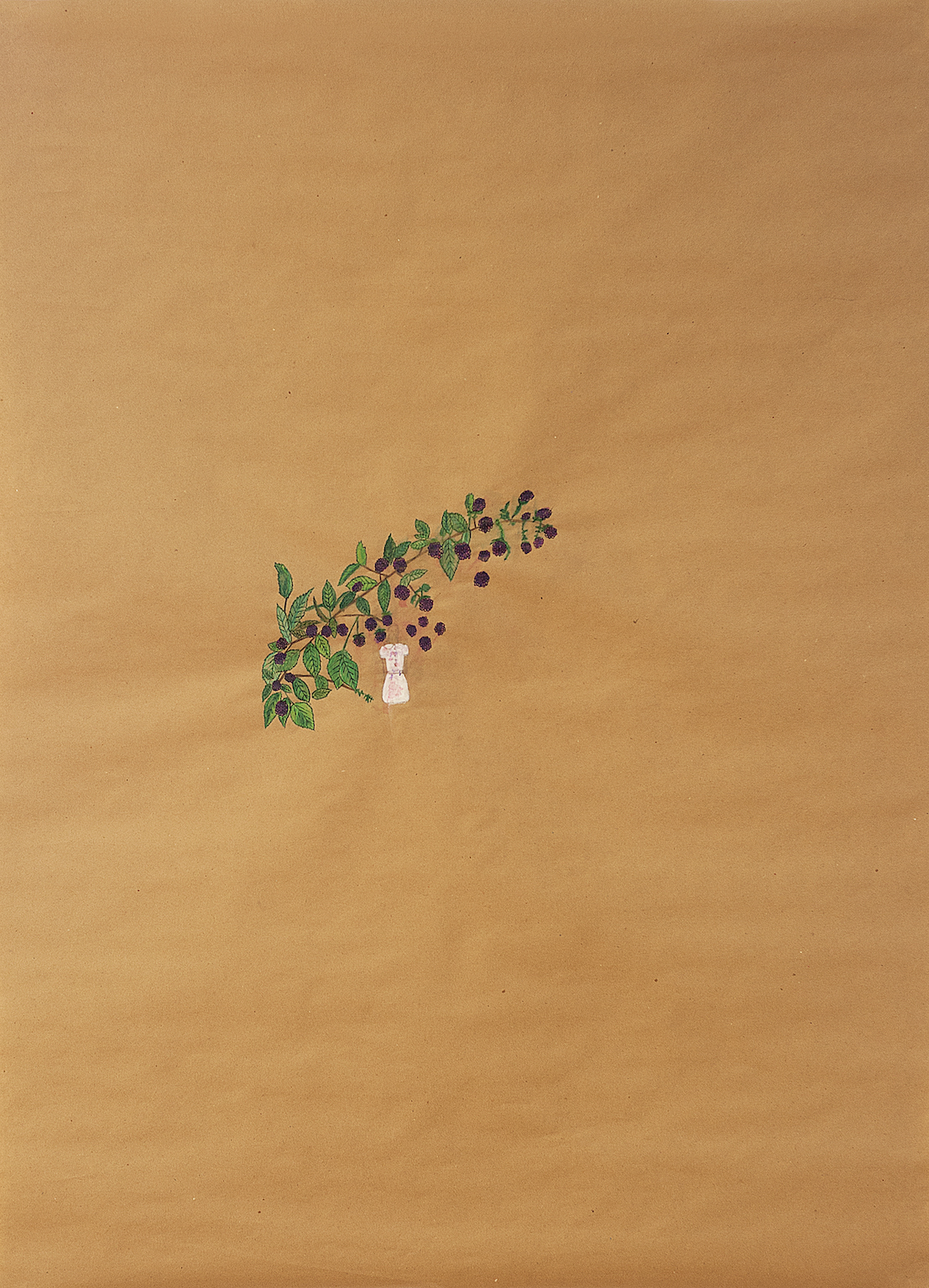

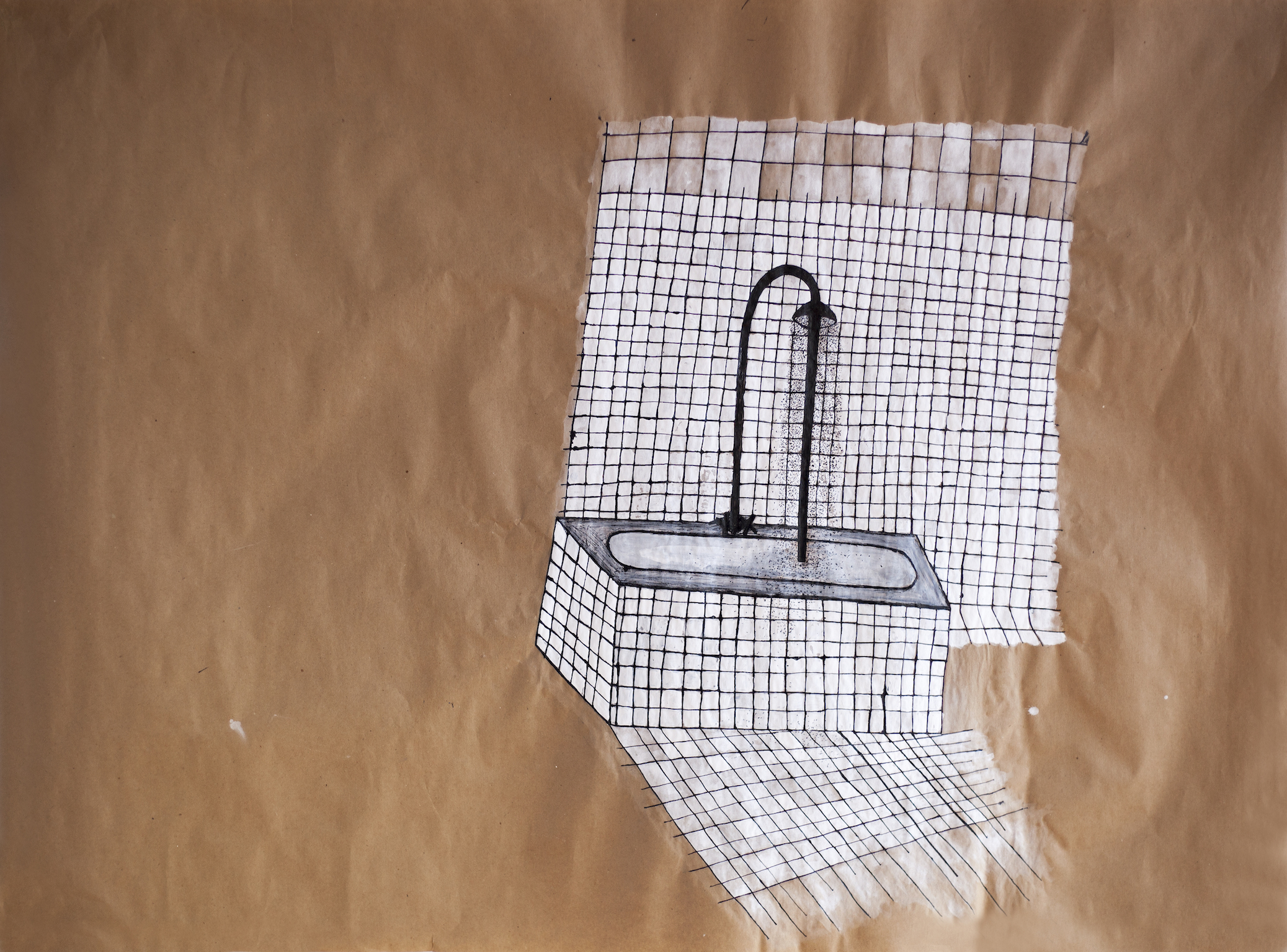

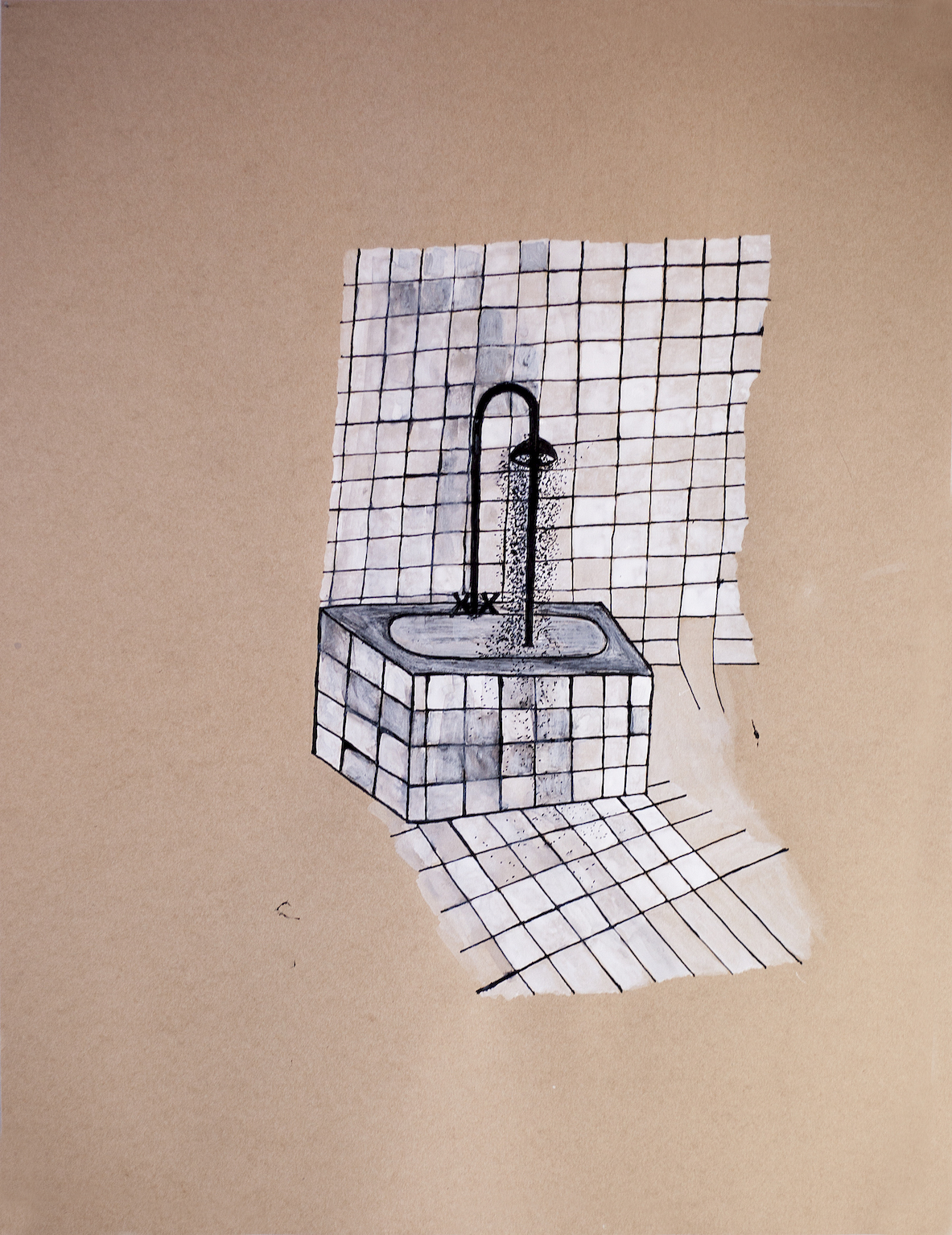

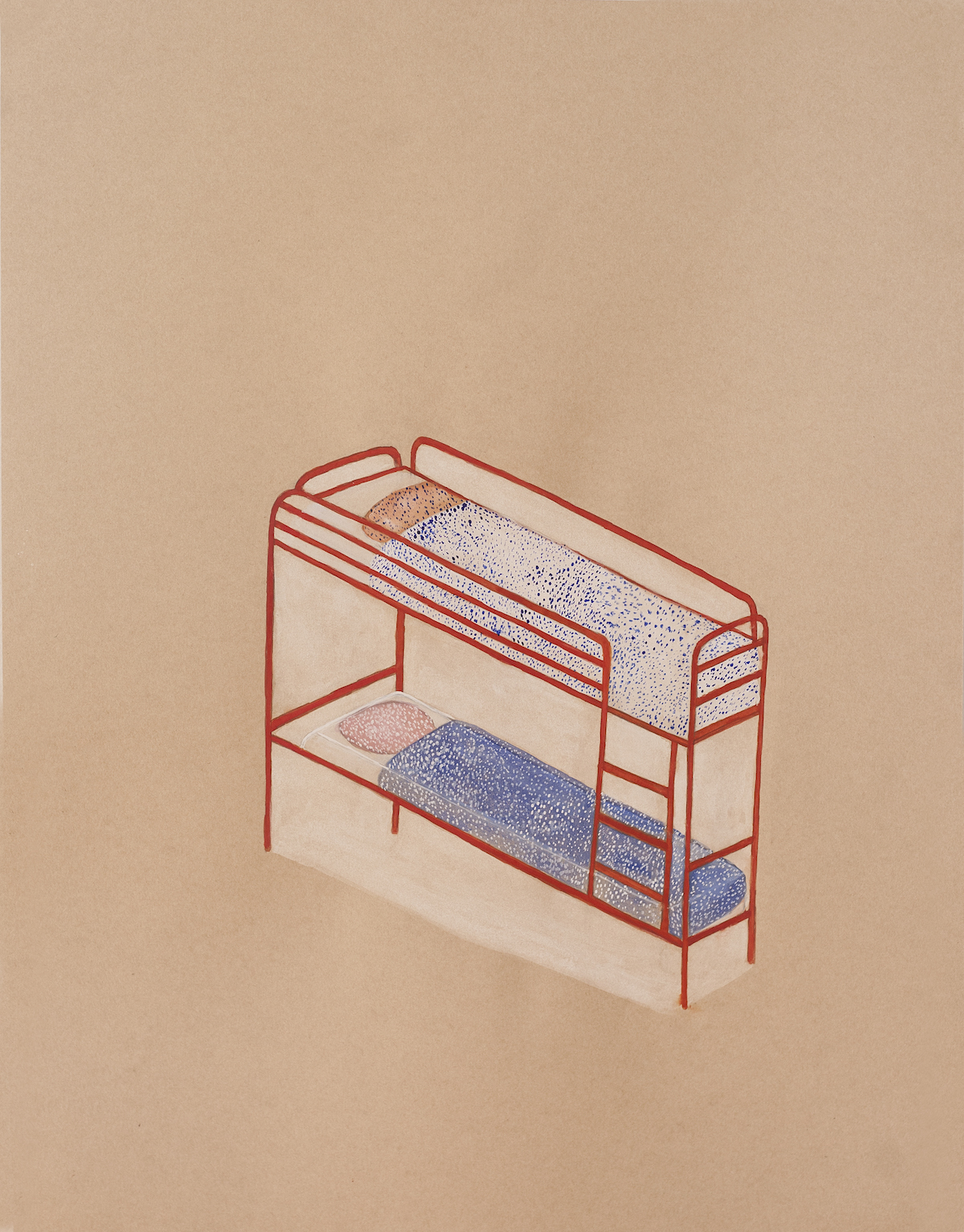

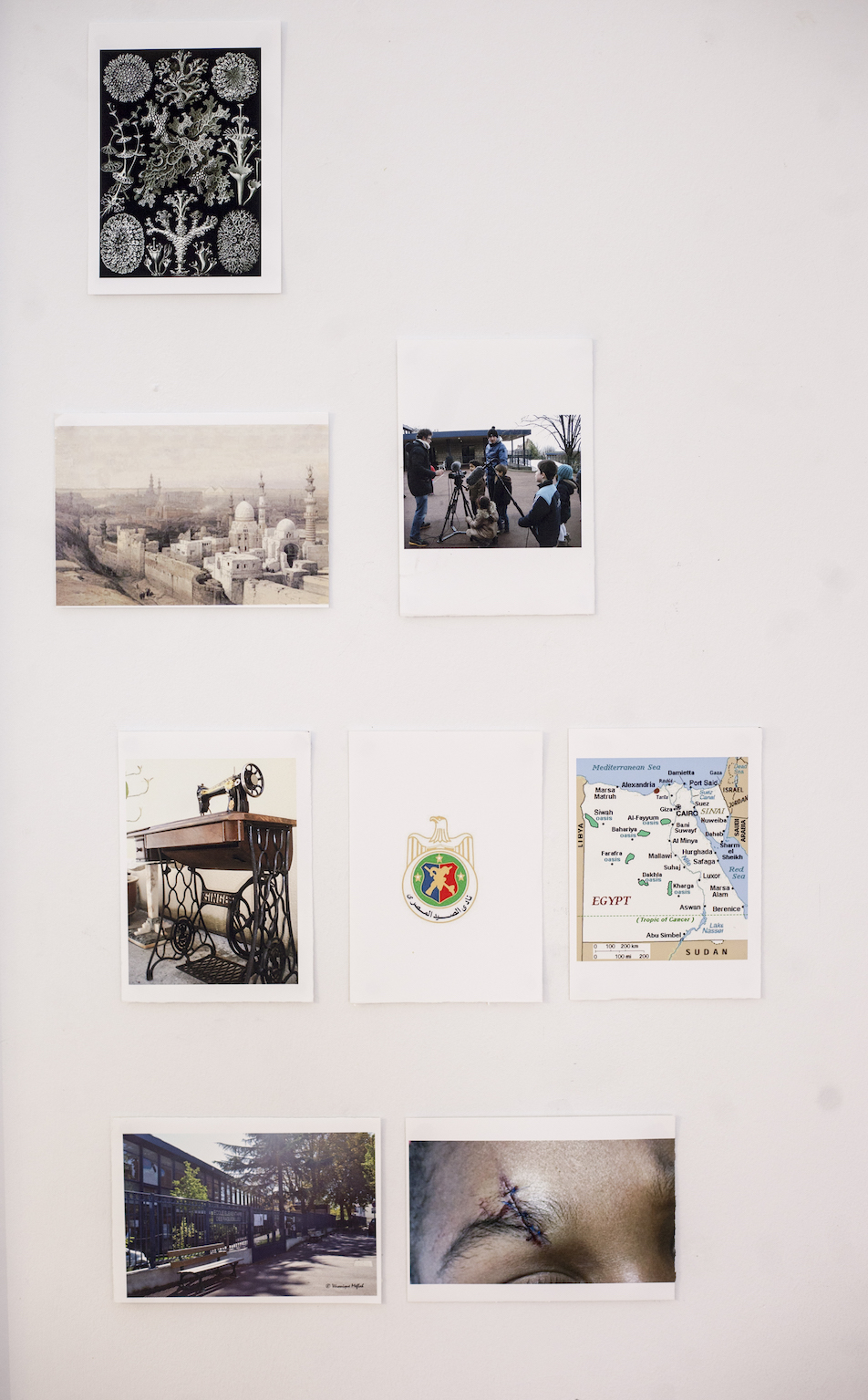

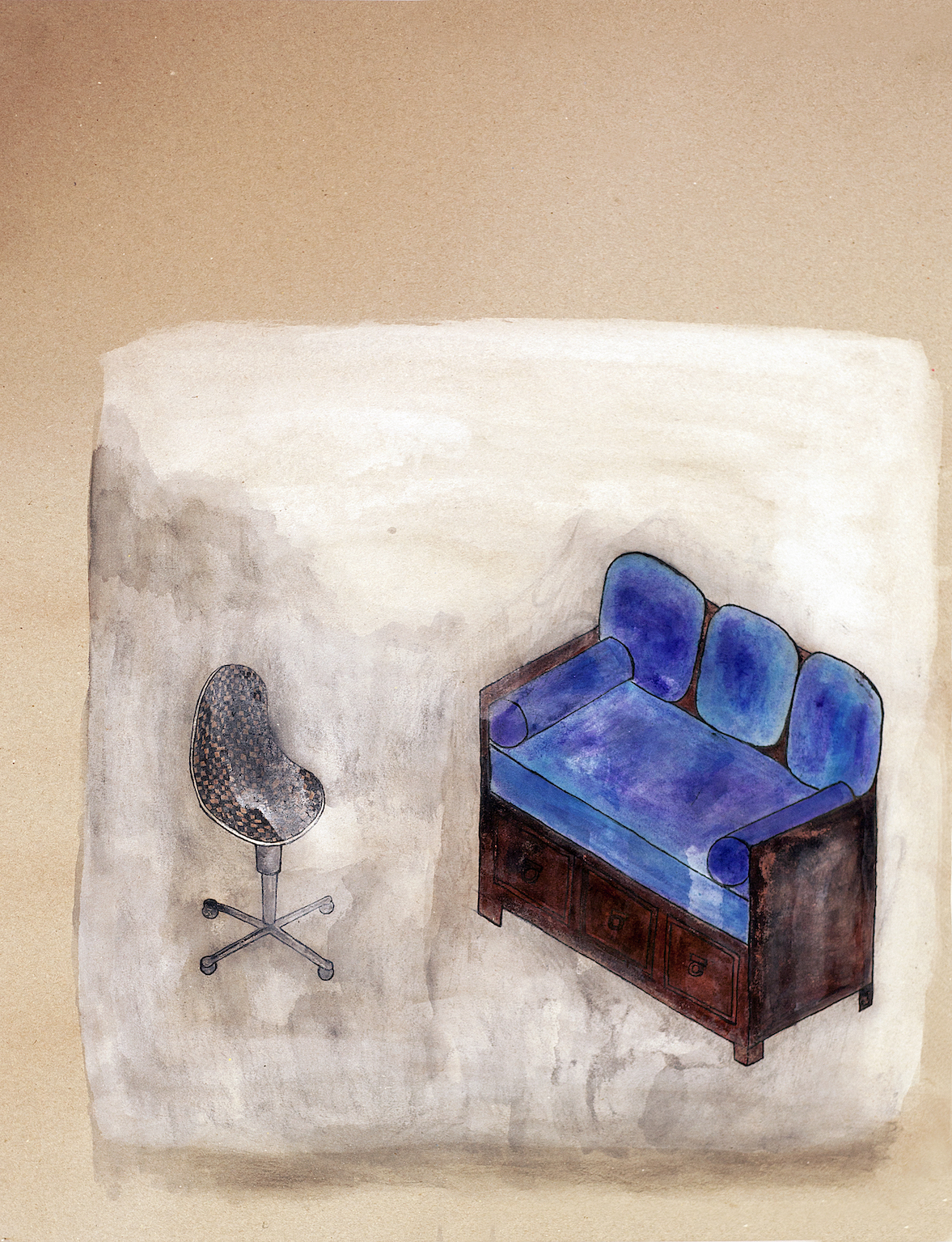

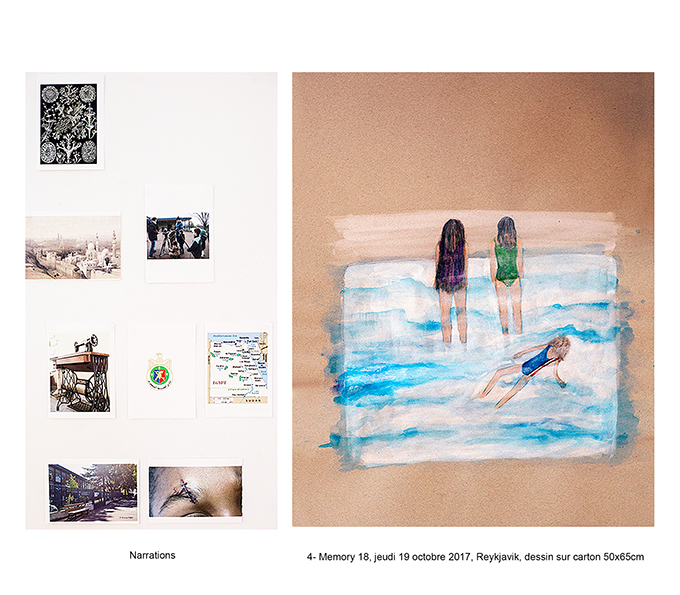

On the walls are drawings of drawings, and sometimes redrawings of redrawings first drawn in 2012. These are from Nermine’s childhood memories. Most of the redrawings are in bigger sizes, but all were redrawn in 2018. Each redrawing is accompanied by images found on the internet that echo the memory according to Nermine’s intuitive logic.

In Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, begun in 1924 and unfinished at the time of his death in 1929, the art historian attempted to map what he calls the “afterlife of antiquity.” He chose images of great symbolic power from Western antiquity and traced their reappearance in the art and culture of later times and places. Following an intuitive logic as well, the atlas roves amongst decades of images, juxtaposing them with seemingly distantly related images, the ‘afterlife’ appears, or, the reality of the image with its own life navigating the epochs in materiality as much as in the memories of the people who embrace them.

In a similar manner, Nermine’s constructions act as an atlas and an echo chamber of thought and memory, making the determinations from the inside and projecting them outward, while the Mnemosyne Atlas operates in the opposite direction. Perhaps in the distant future, we will come to look at the visual culture of the internet, from which Nermine finds the images to juxtapose her redrawings of memories, as a kind of Mnemosyne Atlas of the epoch co-created by every internet user for future generations to ponder with no explanation, just another type of ruin.

Text by Erin Honeycutt